In my last post, I wrote about the college student loan issue from the perspective of the physician family. Related to that point, I also elaborated upon my philosophy about saving for and paying college expenses with minimal debt expansion.

In my last post, I wrote about the college student loan issue from the perspective of the physician family. Related to that point, I also elaborated upon my philosophy about saving for and paying college expenses with minimal debt expansion.

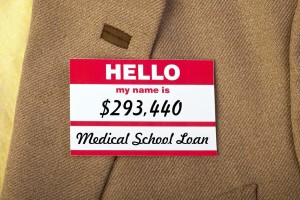

However, the phenomenal accumulation of debt by medical students and residents is another student loan crisis. Unlike the college student loan crisis, medical student loans receive little attention.

I routinely interview physician candidates for my local hospital, and I have been shocked over the years by the enormous amounts of loan debt that they carry with them into practice. $100,000 of debt used to shock me, but no more.

I frequently interview those who are $200,000 in debt. Even worse, I know physician couples who owe a whopping debt of over half a million dollars combined!

I frequently interview those who are $200,000 in debt. Even worse, I know physician couples who owe a whopping debt of over half a million dollars combined!

Now, from the lay person point of view, they will say, “These doctors are going to be making lots of money, and they should be able to pay this back.” As I see it manifested in real life, it is the unintended consequences of this debt burden that is affecting these individuals, medical care, and society in general.

Let’s take the (sadly) low end of the debt spectrum of $200,000. Assuming a low interest rate of 5% and a term of 30 years, that is $1074/month.

So right out of the starting gate, this budding physician is paying a mortgage payment without getting the property to go with it. The psychological burden that goes with the debt burden does not go unnoticed by the new doctors.

They are aware that they will be making more money than during residency. Unfortunately, they will also now have to pay all this money back.

The psychological consequences include the life and professional decisions made to mitigate the debt load. I have seen many doctors and their partners delay starting families “until we afford it.” One young doctor in my practice delayed buying a house for his family because, again, he did not think he could afford one with his and his wife’s combined debt.

The psychological consequences include the life and professional decisions made to mitigate the debt load. I have seen many doctors and their partners delay starting families “until we afford it.” One young doctor in my practice delayed buying a house for his family because, again, he did not think he could afford one with his and his wife’s combined debt.

I see the professional decision-making process affected all the time. I have seen some very dedicated and sincere family practice residents change career choice from a primary care office to a hospitalist or emergency room position because of pay levels as well as hours.

At my local hospital’s family practice residency program this year, only one of nine graduating residents will be pursuing the intended career target of the teaching program: primary care family practice in a rural setting. The vast majority are pursuing ER, hospitalist and even specialty fellowships to improve their pay prospects.

To a person, these individuals say that if pay was at least equivalent, they would choose their original calling of family practice. They feel forced in a sense by their economics to make this choice.

We all know that this pivotal career choice will be self-perpetuating and probably permanent. They are unlikely to backtrack later and take a lower-paying position in primary care to assuage any remaining guilt about their choice.

In the past , I have participated on several panels and statewide advisory groups that met to discuss medical care in the state of Maine. In one group of about fifteen, I was the only general internist, although there was one pediatrician and one family practice doctor joining me to represent primary care.

A frequent topic on these panels was the difficulty in recruiting primary care doctors, which everyone agreed should be the backbone and foundation of any healthcare system. The disagreement usually came down to money. Doesn’t it always?

When I forcefully suggested that the primary care crisis could be solved within 5 years if primary care doctors were paid like cardiologists, my fellow panelists reacted as if I was a bomb-throwing revolutionary. Shock and horror and nervous laughter usually followed my comments.

“Surely, you jest, cardiologists receive so much more training, do more risky procedures, etc.”, they would say. I would usually tell them that I did not mean to denigrate cardiologists or to imply that they did not have extended training.

To me, it was basic math and an economic question: If you want more primary care doctors, and they are truly recognized as a vital part of the health care system (including feeders for the cardiologists), they should be paid significantly more to entice them in their career choice. That is part of how we ended up with so many specialists, isn’t it?

To me, it was basic math and an economic question: If you want more primary care doctors, and they are truly recognized as a vital part of the health care system (including feeders for the cardiologists), they should be paid significantly more to entice them in their career choice. That is part of how we ended up with so many specialists, isn’t it?

Pay doesn’t have to be the only mechanism. Loan forgiveness works too. That is how I paid my loan/scholarship from the U.S. Public Health Service: by practicing for 3 years in a medically-underserved area.

However you slice it, dollars and debt both drive behavior for everyone, including doctors. Depending on altruism will only get you so far.

That is about where we are right now. For all involved, that is not a good place.